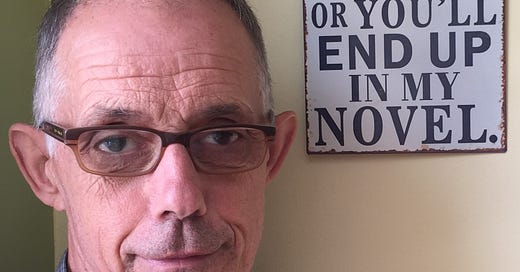

I’ve often envied writers their success. Why do long lines form at literary festivals, their fans holding books to have signed, while I didn’t even get invited to speak?

And then, soon after my spout of envy, quite often those writers I was envying have died.

I am left, writing my furrow, reflecting on envy.

Others, I presume, envy me. While I feel my books are unjustifiably ignored, others will note that they are all published. While I feel the lack of acclaim, others might note my professorship of creative writing and my winning of prizes (but not the really big ones! say I).

As a teenager my favourite places were libraries, and in my twenties bookstores, where I read all the classics, sometimes five novels a week, and developed my pantheon of writers (André Gide, Paul Bowles, Janice Elliot, John Fowles, James Purdy, Patrick White, D.H. Lawrence, Henry James, Jean Genet, William Blake, Jane Bowles) and when my tastes took on a contemporary edge I headed for the rare racks of Picador paperbacks and American imports (the old Books Etc. on London’s Charing Cross Road was great for such treasures).

And then, for periods, I didn’t like going into bookstores at all. Envy soured them for me. Why are all these books stacked on the tables and not mine? (While my books are indeed eventually published they can take years finding a home.)

I’ve known other writers feel the same, and apart from envy there’s a logic in disappointment with bookstores. Their front tables are largely stocked with books that have come out in the preceding weeks. When your literary tastes are formed by reading the cream of what has been published over the preceding centuries, the quality of this welter of the current crop doesn’t cut it. Will any of these books of the last few weeks be held in regard ten years from now? You open the pages, spot the flaws, and turn to the author bio and photo to discover how on earth they got into print.

I’ve grown more sanguine. Knowing how very hard it is to get published I can be pleased for any writer that manages it. They’ve clearly learned some tricks, deployed narrative skills and been professional. The economics of publishing, with the tightest of margins for any profit at all, mean a focus on celebrity and genre. Bookselling is a business and as such it is commercial, and as such it offers me few of the delights that formed my taste.

In my early twenties I took a bet that I would win the Nobel Prize. (Rina, if you’re reading this be in touch. I’ll pay up. The fiver is yours.) And yet that hankering for acclaim persists. I cleared my whole summer for appearances at literary festivals, happy to spread news of the Bishnoi with tales from my book My Head for a Tree. And yet nobody has invited me. Not even Lowestoft’s First Light Festival, which happens on the beach outside the window where I am now writing. (For my previous First Light gig I walked past the large writer’s tent, where a Scottish comic writer was being foul-mouthed for which he was getting a sizeable fee, and located the side-tent for my own free evening appearance to find the venue was being dismantled.)

What to do about my summer of festival non-appearances? Fret? Be envious?

Instead I’m cancelling other events – overseas trips, nights at the theatre, gallery outings. I’m glad of no need to travel. Being a writer isn’t enviable. It’s a condition.

Give me a table to sit at and a window to look out through and I need no other distractions. Neither famous nor dead, I can still write.

For those who miss the chance of meeting me at a festival this summer, there’s always this recording of February’s event in Jaipur. Really, it can’t be bettered.

These last two weeks have brought a little more attention for My Head for a Tree. Scroll had an intriguingly philosophical review from a Bishnoi reviewer – read to the end for his personal take on caring for dogs.

Hie review appreciates the care the book takes in including but not majoring on the story of the gangster Lawrence Bishnoi – choosing to focus on the good rather than the bad people. I’ve been waiting for the feature-length story of the Bishnoi in the Financial Times. Its author Chris Kay learned about the Bishnoi from my book, interviewed me and then went off to meet my contacts. He’s honoured my request to at least mention the book, I get a quote, and he does background the story of the Bishnoi as eco warriors, but of course the full weight of the story is given to the gangster and the film star elements. As one sage friend counselled me, ‘the press is always so’.

It helps me recognize why the press in the west (unlike in India) has paid scant regard to my book. The book is about what I find of value (good people saving the planet) and not what is commercial. Years ago a literary agent offered me lots of money to write a true crime book about a family of German cannibals. I declined.

Publisher’s Weekly, the magazine for the book trade in America, has just given My Head for a Tree a fine review. And I thank them. Here’s the highlight: ‘Goodman profiles his subjects and relates his historical anecdotes with the verve and amiability of a travel writer. It’s an infectiously buoyant and upbeat account of committed environmental activism.’

What charms me is their sense of my ‘amiability’. I’ve had reviews in the past that have been venomous about my character. This new adjective serves as balm.

At an Earth Day event in Santa Barbara last month, when my husband James Thornton and I made a joint appearance, I spoke of a difference between us. I use narrative in order to understand things. James uses narrative to communicate what he’s understood.

This Substack has taken a few forms before settling on this ‘Letters Home’ version of itself. I sat down today not knowing what would emerge. After writing, I have a clearer sense of a writer’s life and of dilemmas facing book lovers in bookstores.

Hopefully you have too.

I do recognise that ambivalence and disappointment in bookshops. At least with poetry few shops have a substantial poetry section; then it's just the big ones that disappoint.