On Netgalley, and letting a gay spirit into the world

Is it good to have five AND one star reviews?

Placing a book on Netgalley is like giving a city a free pass to walk through your garden. Some will keep to the footpaths and sniff the lavender. Others will trample your roses and kick down your fence. Both types of visitor are having fun. One of them is kind and appreciative, and one leaves you bruised and wondering why you bothered.

The principle of Netgalley is that the publisher / writer pays to give readers a preview of a new book. The aim is to build word-of-mouth.

It works for books that fit a genre – so readers get what they expect. Satisfy their expectations and you get five stars.

Don’t meet their expectations and you risk getting hammered, trolled, the reader turning judgmental.

As a publisher I tend to guard our authors and not pay to go down that route. Barbican Press’s books usually defy genre expectations – they offer great storytelling that veers into dangerous territory. Our books can excite but also roil readers – they trip into your psyche and can disturb you. I’ve claimed that I want my books to get both five and one star reviews, to goad as well as delight.

Of course secretly I’d feel warmed by a host of five stars, but I’ve managed to get the mix.

I viewed Lessons from Cruising as sufficient genre to try Netgalley out, on the reduced rates you can obtain through membership of IBPA. Its genre? LGBTQI+ short fiction (specifically gay).

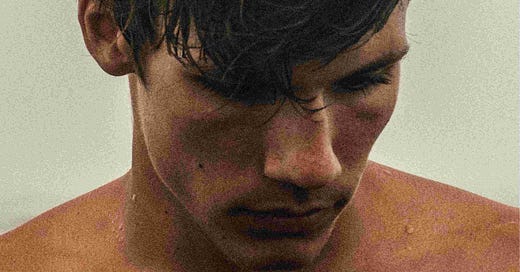

The book’s title comes from a story title within the collection. The cover image is a beautiful dark-skinned young man by the shore. Water / swimming / the sea, and being gay-themed, is what wraps all the stories together as a collection.

That title and cover image seemed innocent. Early reviewers on Goodreads felt they were deceitful picks somehow. I got my one and two star reviews.

Then, blissfully, other readers came on board. They had paused between stories in the collection, tearful, taking time to absorb each one before moving on. People had different favourites but many enjoyed the whole.

Authors have to be thick-skinned, but of course we’re not.

The short story form gave me a refuge to express my gay identity in a world where most people hated and reviled that aspect of me. One thread, stories about Arnold, came from coming to know about what was then termed the ‘berdache’ tradition in Native American culture. In simple story-telling terms, a baby boy was laid down with a doll on one side and a bow and arrow on the other. If he turned away from the weapon and toward the doll, so revealing his gay side, his parents rejoiced. Their family was complete, they needed no other child, for this one brought the qualities of refinement, fun and compassion that they and their community needed.

What would that tradition be like if supplanted to western culture? That’s what I set myself to imagine. Coming out to my mother left me unable to speak for several days. My stepfather told me that my being gay and in a relationship was the very worst news she could have received (so a terminal illness would have been brighter news). In contrast, the parents I imagined for Arnold rejoice at his gayness. As do his neighbours his teachers. His schoolmates.

A British TV documentary series, Michael Apted’s Seven-Up traced British children of my age, starting when they were seven and revisiting them at seven year periods to see how they were growing into the world. I loved and identified with the series but none of the children went on to reveal themselves as anything but straight. My story Arnold’s life added that element, moving forward in seven year leaps, from seven to forty-two.

The collection rounds off with a tale I wrote when the pandemic closed me indoors with a view of the North Sea. This was in Lowestoft, hometown to the composer Benjamin Britten who grew up across the road and shared the same view. For years I had pondered one of the most significant missing chapters in literature: in Herman Melville’s Billy Budd, the magnetically beautiful Billy Budd has struck dead a sailor who goaded him. Locked in a stateroom, Captain Vere goes in and announces to the young man the verdict of the ‘court’: that he will be hanged. That scene inside the stateroom is the one that’s missing from the book. It’s missing from Britten’s operatic version too, with E.M. Forster’s libretto. The encounter between the captain and the sailor was clearly profound, affecting both characters deeply. What happened?

I sat at a table, stared out at the sea, picked up a fountain pen and rewrote Billy Budd from Captain Vere’s perspective. In his life Herman Melville was distinctly non-binary, married to a woman and wracked by unrequited male love. and in my version Captain Vere’s own yearnings find expression in his letters to a friend. It took a century after Melville, and decades of my own life, and ultimately the clear space granted by a pandemic, to let the story be told.

Lessons from Cruising is my garden. You’re welcome to come in and wander round. Feel free to walk on the grass. Perhaps pick a bunch of six favourite flowers. Bring friends for a picnic if you like.

Just don’t tread on the pansies.

Writing tip:

Don’t be afraid of repeating your character’s name instead of a pronoun. It can spare the reader having to work out who the pronoun (e.g. he / she / they) refers to. When they have to trawl their way back in the text to do that, you’ve lost them. The magic pauses.

I’m still enjoying reading these stories Martin. And particularly relishing the life given to Arnold after all those closeted years ❤️